The recent journey of about 25 Eastern Pennsylvania Annual Conference members to the site of the historic Carlisle Indian Industrial School took them a distance of only about 100 miles. However, their daylong tour also took them back more than 100 years into the difficult history of that institution.

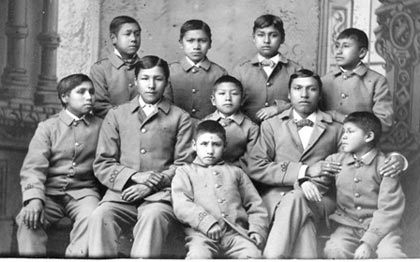

Carlisle was the first of 26 off-reservation industrial schools created by the U.S. government to acculturate Native American children and youth by teaching them "acceptable" customs of mainstream American society. It opened in 1879 with 82 boys and girls. By the time it closed in 1918, more than 10,600 students, ages 6 to 25, had passed through its gates, their lives and their families back home forever changed – for many, changed for the worse.

The conference Committee on Native American Ministries (CONAM)sponsored the visit.

The school was built on an abandoned Army base. Today, the National Historic Landmark site has returned to that original use as the U.S. Army's War College and barracks. But the school's memories, including heroes like the famous Olympic athlete Jim Thorpe, are forever present, as are the white gravestones near the entrance marking where hundreds of former students are buried.

CONAM members Sandra Cianciulli and Barbara Christy recently joined advocates in saving the former school's farmhouse, a key part of its legacy. They prevailed over attempts in 2012 to demolish and replace the timeworn building with additional Army base homes. Over the next few years, the farmhouse, whose historical significance was uncovered through research, will instead be renovated and, perhaps, converted into a museum or visitor center to share the compelling story of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

During visits to the nearby Cumberland County Historical Society and the Army base, a guide gave the group a look into Carlisle's history. It was the brainchild of Capt. Richard Henry Pratt of the U.S. Army Cavalry. After the Civil War, Pratt fought against American Indians in the West and brought prisoners back to Fort Marion in Florida.

Local Quaker women taught them to read and write. Released prisoners went to college or agricultural school. Pratt believed assimilation into mainstream white culture – teaching children to speak English, to dress as whites did and to learn useful trades – would give Native Americans their best chance for survival.

However, this was far from the truth. Native American children were forced to conform to the white world, thus losing their heritage. Ten percent of the children that were taken away from their parents and "taught" died at the school because they were not cared for like the white children. Although the school was known for its sports and music departments, the horrors that went on there have not been forgotten.

Many who survived Indian industrial schools later repressed painful memories, just as they had repressed their tribal customs. Forced to reject their cultures, they were prepared for assimilation into a mainstream culture that, ultimately, rejected them out of racism. The result for many was alienation, shame and generational trauma.

As the CONAM tour group boarded the bus to return home, some participants recalled the 2012 General Conference resolution, "Acts of Remembrance and Reconciliation with Native Americans." It charges the denomination's Council of Bishops and annual conferences to engage in an ongoing process to improve relations with indigenous peoples through acts of repentance.

Molly Dee Rounsley and John W. Coleman

One of six churchwide Special Sundays with offerings of The United Methodist Church, Native American Ministries Sunday serves to remind United Methodists of the gifts and contributions made by Native Americans to our society. The special offering supports Native American outreach within annual conferences and across the United States and provides seminary scholarships for Native Americans.

When you give generously on Native American Ministries Sunday, you equip seminary students who will honor and celebrate Native American culture in their ministries. You empower congregations to find fresh, new ways to minister to their communities with Christ's love. Give now.